- HOME

- New Product and Technology

- Supersulfide Research Reagents : Glutathione Trisulfide and NAC Polysulfides

Supersulfide Research Reagents : Glutathione Trisulfide and NAC Polysulfides 2025/12/24

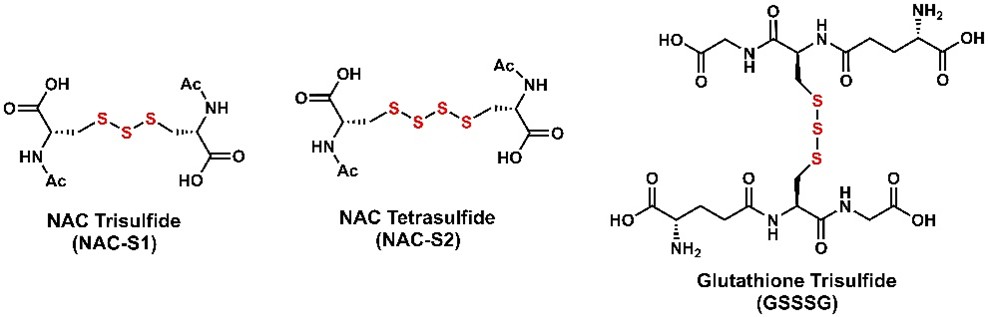

Supersulfides are an emerging class of molecules attracting increasing attention in life science research. Here, we introduce Glutathione Trisulfide (GSSSG) and NAC polysulfides, which are highly useful for analyzing sulfur metabolism pathways and investigating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities.

The Research Potential of Supersulfides

Understanding oxidative stress, inflammation, and signal transduction pathways is a central challenge in life science research. Supersulfides have recently attracted significant attention in this field.

Recent studies have demonstrated that these molecules exhibit significantly stronger antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities than conventional sulfur-containing compounds, making them powerful research tools that greatly expand experimental possibilities.

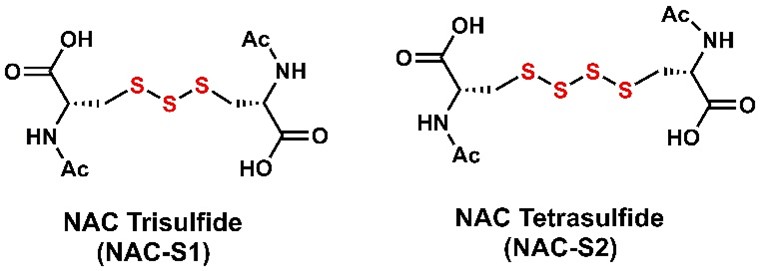

We provide the following polysulfide derivatives related to supersulfides as research reagents:

- NAC Trisulfide (NAC-S1)

- NAC Tetrasulfide (NAC-S2)

- Glutathione Trisulfide (GSSSG)

What Are Supersulfides?

Supersulfides are molecules containing polysulfide chains formed by sulfur catenation, allowing for diverse reactivity. In biological systems, sulfur atoms are added to the thiol groups of cysteine and glutathione (GSH), forming hydropolysulfides such as CysSSH and GSSH [RS(S)nH], as well as polysulfides such as GSSSG [RS(S)nSR].

Numerous important findings on supersulfides have been reported by the research group of Professor Takaaki Akaike at Tohoku University. His group demonstrated that supersulfides are not mere metabolic byproducts but are actively synthesized by CARS2 (cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase), and that they play essential roles in antioxidant defense and signal transduction1,2).

These studies indicate that supersulfides are key regulators of oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular signaling. Their roles are expected to contribute to the elucidation of biological phenomena, disease mechanisms, and the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Physiological Roles of Supersulfides

Supersulfides are extremely reactive and exert diverse physiological functions depending on their reaction partners.

Potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities

They efficiently react with reactive oxygen species (ROS), free radicals, peroxides, and metal ions, thereby exhibiting strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects3,4).

Regulation of signal transduction

Supersulfides react with electrophiles such as 8-nitro-cGMP to reduce their reactivity, and also persulfidates protein cysteine residues, thereby contributing to the regulation of redox signaling, transcription, and metabolism1,7).

Chemical Properties of Supersulfides

Under physiological conditions, supersulfides undergo repeated hydrolysis and reactions with nucleophiles and electrophiles, dynamically altering the number of sulfur atoms and generating a wide variety of molecular species8).

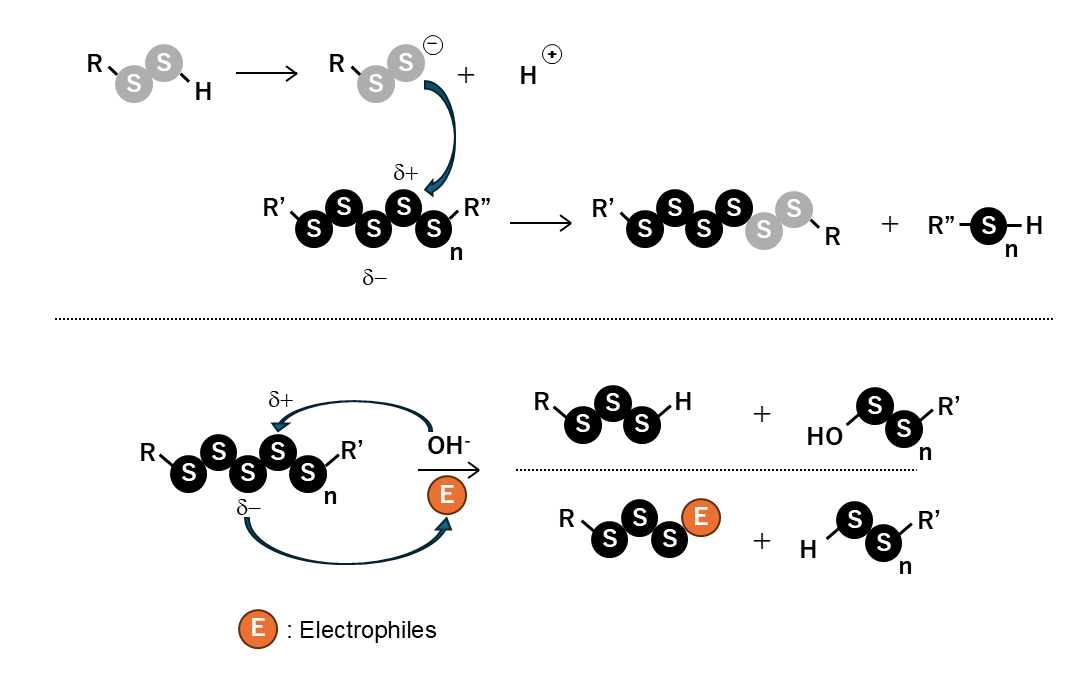

Dual nucleophilic and electrophilic reactivity

Hydropolysulfides [RS(S)nH] normally behave as electrophiles; however, in the deprotonated persulfide anion state (RSS⁻), they function as nucleophiles. This dual reactivity enables reactions with a wide range of chemical species.

High reactivity at physiological pH

Catenation alters the electronic environment and lowers the pKa compared with the corresponding thiols. For example, while GSH has a pKa of approximately 8.9, GSSH has a significantly lower pKa of approximately 6.99). Consequently, GSSH exists as a nucleophilic persulfide anion even under physiological pH, exhibiting high reactivity10).

Dynamic sulfur transfer reactions

Polysulfides [RS(S)nSR] exhibit polarized sulfur–sulfur bonds and are in hydrolytic equilibrium with water under physiological conditions. Through reactions with nucleophiles and electrophiles, sulfur atoms increase or decrease in number while undergoing transfer, rearrangement, elongation, and degradation, resulting in a cascade of supersulfide species.

Fig. Chemical properties of supersulfides

Hydropolysulfides [RS(S)nH] exist in equilibrium between the protonated RSSH and persulfide anion RSS⁻ forms. Because GSSH has a pKa of approximately 6.9, it exists as a highly nucleophilic persulfide anion under physiological conditions. Polysulfides [RS(S)nSR] readily react with nucleophiles (including persulfides and water) and electrophiles due to charge polarization. As a result, supersulfides undergo chain reactions to generate diverse molecular species.

Featured Research Reagents

NAC Trisulfide (NAC-S1) / NAC Tetrasulfide (NAC-S2)

- NAC Tetrasulfide (NAC-S2) efficiently generate intracellular supersulfides (e.g., GSSH, GSSSH) via reaction with endogenous GSH.11).

- Enhanced Potency (NAC-S2) NAC-S2 exhibits stronger antioxidant activity and polysulfide donor capacity compared to NAC-S1.

- Applications Analysis of sulfur metabolic networks, endogenous supersulfides, and signal transduction pathways12,13,14).

GSSSG(Glutathione Trisulfide)

- Endogenous Polysulfide Donor A naturally occurring, GSH-derived polysulfide that exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in cells and tissues1).

- High Solubility & Stability Highly water-soluble (contains TFA counterion) and verified stable as a powder at −20 °C.

- Applications Ideal for evaluating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy in various disease models15,16,17).

| Code | Product Name | Quant |

|---|---|---|

| 3432-v | Glutathione Trisulfide | 5 mg |

| 3433-v | NAC Trisulfide | 5 mg |

| 3439 | NAC Tetrasulfide | 5 mg |

The Future/Impact of Supersulfide Research

Supersulfides have become an increasingly important topic in life science research. Their high reactivity, dynamic chemical behavior, and diverse physiological functions are expected to greatly contribute to the elucidation of biological phenomena and disease mechanisms.

The research reagents introduced here are powerful tools for efficiently analyzing the biological actions of supersulfides. We encourage their use in studies of oxidative stress, inflammation, and signal transduction.

- T. Ida et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 111, 7606-7611 (2014).

- T. Akaike et al., Nat. Commun., 8, 1177 (2017).

- U. Barayeu et al., Br J Pharmacol., 183, 115-130 (2023).

- T. Zhang et al., Front.Immunol., 16, 581385 (2025).

- Y. Yamada et al., J. Biol. Chem. 298, 104710 (2023).

- M. R. Filipović et al., Chem. Rev., 118, 1253–1337 (2018).

- T. Akaike et al., Free Radic.Biol.Med., 222, 539-551 (2024).

- Seikagaku, 93, 708-716 (2021).

- H. Li et al., Redox Biol., 24, 101179 (2019).

- Seikagaku, 93, 613-620 (2021).

- T. Zhang et al., Cell Chem. Biol., 26, 686 (2019).

- H. Takeda et al., Redox Biology, 65, 102834 (2023).

- X. Sun et al., Immun Inflamm Dis., 11, e959 (2023).

- X. Li et al., Int. Immunol. 36, 641–652 (2024).

- H. Kunikata et al., Sci. Rep., 7, 41984 (2017).

- H. Tawarayama et al., Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm., 30, 789–800 (2020).

- H. Tawarayama et al., Sci. Rep., 13, 11513 (2023).